Sometimes things just click into place. Here’s an example: a while back I had an idea for a short story which was inspired, in part, by the steel works at Port Talbot, Wales. You can see a photograph below. I’d always loved the idea of a place like this, perched on the very edge of the land, being one of the last enclaves of the human race after some unspecified apocalyptic event.

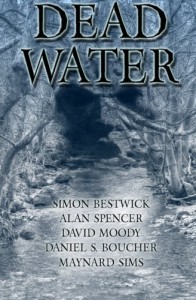

And then I was contacted by a friend of mine, DAN BOUCHER, who is one of the minds behind www.thenovelblog.com. Dan’s partner in crime on the blog, PETER MARK MAY, runs HERSHAM HORROR BOOKS and releases regular PentAnths – themed anthologies featuring stories from five invited authors. So I landed myself an invite to contribute to DEAD WATER, and my Port Talbot-inspired story seemed to fit the bill perfectly.

We all need water to live, but what if that life giving body was not so friendly after all?

The book is available now (Amazon.com / Amazon.co.uk / Kindle US / Kindle UK – more links to follow) and features my story THE LUCKY ONES alongside tales from Dan, MAYNARD SIMS, ALAN SPENCER and SIMON BESTWICK.

Click the link below the steelworks picture for a brief snippet.

William is one of the lucky ones. He knows this, because his mother tells him so, several times every day. One of the old men told him too, that time he dared to question. The old man hit him across the face, bloodied his nose. ‘You’re safe, you’re warm, you’re alive,’ he shouted at William when they caught him trying to get away. ‘Things don’t get better than that anymore.’

But William’s not so sure.

The factory is home. It’s a man-made island; a mass of concrete walls and metal pipework, surrounded by water on all sides. The acidic seawater is devoid of all life. Toxic. Poison. It isolates them from everything else, leaves them vulnerable and exposed.

This place used to be an immense steel production facility, connected to the mainland by road and rail. Not anymore. Not for a long time. Those connections to the homeland have been permanently severed.

The factory itself used to be many times this size, once employing more people than are probably left alive in total now. Now the last vestiges of industrial activity are confined to one end of the complex, with the remains of the isolated population eating, learning and living, away from the furnace, the chimneys, the exhaust fumes and the noise.

The decline began when war broke out, so long ago that the reasons for the fighting have been all but forgotten. Our brave men and women are still out there, though, risking their lives on foreign, polluted shores, to preserve the freedom of those who keep the factory fires burning. William’s most recent letter from his father, received only last week, said his division had secured an important tactical advantage in the preceding days, and that the end of the fighting would almost certainly soon be in sight.

It’s a funny old beast, this place; a safe and reassuring home, yet with all the restrictions and inflexibility of a prison. William’s teacher used to always use a particular word to describe it. Symbiotic, that was it. The factory needs its people, and the people need their factory, she’d always say, and she was right. You can’t have one without the other. The people keep the place working and keep the furnace lit and stoked, and in turn the factory keeps them warm and dry, safe from what the rest of the world has become.

But William is still not convinced, no matter what they tell him.